The Value of a Novel’s First Draft to the Final Product

Completing a book typically requires a lot of rewrites, so what is the value of the first draft? The first draft can be the most important draft, depending on the final product. The National Novel Writing Month, after all, was started to get people to write at least 50,000 words.

Since 2006, more than 470 books have been written during this month that were later published with traditional publishers, and more than 100 books were self-published. Some books written in this period have reached the New York Times Best Seller List.

How the First Draft Benefits the Completed Product

The Writer Writes It Down

This is the first step of every effort. In the writing of the draft, the creative process unleashes the characters that will live in the story and may even develop a life of their own that was unplanned at the start.

The Draft Enlightens the Writer about What Works

It is where the writer tells the story but after completion may find it is imbalanced in some way. Imbalance can reveal, for instance, that some of the characters do not belong in the story, or that the story is missing a character, or a character needs to become more dominant.

In the writing, the writer may decide to change the intended story line or the point of view, and add more or less background information. To keep the writing going and creative juices flowing, it is better to make notes about changes and keep moving forward to tell more of the story.

In the First Draft, the Writer Decides the Book’s Genre

The writer may decide the story is one genre, but in writing this draft may decide to change it. It is an explorative venture that enriches the process of refining the final product.

After the First Draft

In completing the first draft the writer becomes an author, even if not a published one. An important milestone is passed en route to the final product. A completed first draft means it is not a false start, even though this draft is still an imperfect product.

The potential to be a writer has been realized; the story has been told. Next, the first draft needs to be refined through the editing process and however many rewrites and content discarding that involves.

After completing the draft, the writer should take time off before coming back to edit to make this process more effective. Yes, some writers edit during the first draft, but for other writers editing dampens the creative process.

- Published in Writing & Editing Resources

Immigrant Writers Aspiring Immigrant Writers Should Read

Immigrant writers have a rich reservoir of inspiration that connects their personal lives and heritage. Readers travel to other countries vicariously through the descriptions in the books they read. The presentation of a lived experience enriches readers. The variety of immigrant writers in America has widened their readers’ exposure to other cultures.

Immigrant Authors Open Readers’ Minds about Immigrants

Reading makes readers more empathetic when they become absorbed in characters and experience their feelings. America is transitioning into a new era, the minority-majority era, which demands more empathy towards others so that all Americans work together for the betterment of their communities, states, and country.

The Diversity of Immigrant Writers in America

Chinua Achebe, an immigrant from Nigeria, wrote “Things Fall Apart,” describing the struggles of Nigeria’s Igbo tribe as their way of life was changed by white Christian colonists. Ghanaian-American Yaa Gyasi’s “Homegoing” presents the slave trade and its legacy through the story of two sisters and their descendants over a period of 300 years. Aspiring writers can see how the author skillfully manages to write a story of epic scope that is not compromised by excluding significant detail.

Jhumpa Lahiri’s fiction explores themes of immigrant life in America, duty, family, and freedom. Her debut short story collection, “Interpreter of Maladies,” was awarded the Pulitzer Prize; and her story about the children of immigrant parents, “The Namesake,” was made into a movie. Piyali Bhattacharya’s book of stories by South Asian American women, “Good Girls Marry Doctors: South Asian American Daughters on Obedience and Rebellion,” presents their work in an easily digestible essay collection.

Art Spiegelman’s serial comic, “Maus,” about life in Nazi Germany and the relationship between a Holocaust-survivor father and his son, brought serious respect to the graphic novel medium. The graphic novel, “The Best We Could Do,” by Thi Bui is about how displacement and immigration affected a Vietnamese-American immigrant daughter and her parents. Shaun Tan’s graphic novel, “The Arrival,” captures the immigrant experience from arrival to integration to growth.

Gene Luen Yang’s “American Born Chinese” is a graphic novel about a young student and the issues of identity that confront him in school. Christina García’s “Dreaming in Cuban,” and other works present the Cuban-American experience. Janine Joseph, an immigrant from the Philippines, writes stories and poetry about growing up undocumented in America.

The poetry of Vietnamese-American poet Ocean Vuong is spellbinding and deep. Nigerian-British novelist Helen Oyeyemi often uses fairy tales and fables in her novels.

Immigrant writers can be an important part of building a more empathetic and diverse society. If you are an aspiring immigrant writer, you will benefit by checking out the stories of other immigrant writers for inspiration and guidance.

- Published in Writing & Editing Resources

Book Writing Software and Publication Issues

Are you ready to write a book? Do you think getting your book published will be the most difficult challenge? Actually, the hardest part is writing a book, as there are more opportunities than ever before to publish a book. There are also more tools available to make the writing task easier.

Before you begin writing, you need to have your writing tools ready for use. Which one will work for you? The optimal writing tools provide the support a writer needs to become productive.

Software Tools for Writers

Will you use Word, Pages, Nisus Writer Pro, Scrivener, or something else? Scrivener is made for writers and is ideal for long projects. It can also output books directly to self-publishing services. Storyist offers an alternative to Scrivener. Its iOS version enables writing on the go. Storyist also has tools that help writers who intend to self-publish their work.

If you want to use a free tool, consider the open source Bibisco tool for Windows and Linux users. Its capabilities include character development tools and book and scene organization tools. InDesign and Photoshop are useful for creating the visual aspects of the book.

Mobile apps permit writing on the go. Word for iPad, Storyist for iOS, Pages and Quip for iOS, and Google Docs for iOS and Android are all available. OneNote, Evernote, and Pocket are all helpful for research. Trello, a project management tool, helps writers track their work and become more consistent. Go ahead and see what else you can use. Novel Factory, creative writing and other software offer writers many choices.

Self-publishing Sites for Writers

If you plan to self-publish, you have several options. CreateSpace, Author House, and Xlibris are cost-free or come with charges for more supportive services. EBook distribution choices vary with Smashwords, Draft2Digital, PigeonLab, EpubDirect, BookBaby, and eBookPartnership.

Book Proposals for Nonfiction Books

If you want a publisher to publish your nonfiction book, you will need to create a book proposal to pitch your book idea. A book proposal explains why your book, or book idea, is a marketable product. It can be 50 pages or more. Seasoned writers create the proposal before drafting the book. But, new writers may find it easier to write the book before creating the proposal. Do what works best for you.

A Novel Synopsis for Publishers

Agents or publishers want to see what happens in the novel. The synopsis contains the narrative arc of the novel from beginning to end. A novel synopsis is useful because it reveals weaknesses in the plot, characterizations, and/or the structure of the novel. The synopsis also reveals how unique or interesting the story is.

Writing is a process that begins with the basics, before the writer’s creative skills are exercised. Being organized, knowing how you want to publish the book, and preparing what is needed will make the process productive for you.

- Published in Writing & Editing Resources

Why Finding a Literary Agent Still Matters Today

Few major publishers take submissions seriously if they are not received through a literary agent. As revealed by the 2014 Digital Book World and Writer’s Digest Author Survey, agented authors received substantially higher median advances and earnings. Traditional publishers also depend on agents to be reliable guides for writers.

What Literary Agents Do For Writers

The main purpose of an agent is to sell manuscripts to publishers. Agents are professional salespeople but also career and writing guides for writers. To be successful at their manuscript sales job they need to have great contacts.

Agents provide pre-submission editorial work. This means perfecting the work, not fixing a half-baked project. Afterwards, agents oversee the publication process while advising their writers throughout the process.

As part of their manuscript-selling role, agents need to know which editors are suitable for particular projects, and which publishing imprints are most suitable for the works. Agents must also be able to run auctions capably. In an ideal situation, multiple publishers will bid for the work. The agent advises the best course of action, if the manuscript is unable to attract multiple offers.

An agent must be experienced in negotiating a contract that reflects the best current practice for e-royalties, reversion clauses, and related matters. This technical aspect of price negotiations requires expert knowledge. An agent should know how to organize the sale of other rights, such as foreign language, TV and movie rights, with in-house capability or through partners.

Preparing a nonfiction book proposal or novel synopsis is an important preparatory step for the process of securing an agent.

Nonfiction Book Proposals

Book proposals take time to draft and can be 50 or more pages long. Experienced writers submit the proposal before writing their book. Novice writers may prefer to write the book before drafting the proposal. The proposals explain why the manuscript, or idea, is marketable.

A Novel Synopsis for Fiction

The synopsis reveals what happens in the novel and covers the narrative arc of the story. It reveals how fresh or interesting the story is and may reveal structural weaknesses that need to be corrected before submitting the work to publishers.

Finding an Agent via the Publishers Marketplace

The database of deals at the Publishers Marketplace provides useful information about which agents to target. The database reveals which agents have sold what books to which editors. The deal information also reveals the prices the manuscripts were sold for. The available information is useful for finding appropriate agents, and as a resource that can be used to entice agents’ interest.

Literary agents bring the value of monetary and non-monetary benefits to a writer’s career. If your book is of niche interest, such as an educational or professional work, you may not need an agent. However, you will have the advantage if you are able to obtain an agent.

- Published in Writing & Editing Resources

The Establishment of the London Police Inspired the Creation of Detectives in British and American Crime Fiction

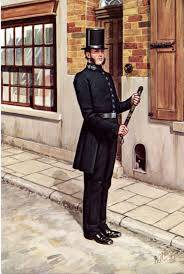

Until 1829, crime prevention in London was the responsibility of a cadre of men working for magistrates’ courts, parishes, or local divisions. In response to increasing crime and unrest, a parliamentary committee in 1812 recommended putting a unified force throughout the capital, although the Metropolitan Police wasn’t formed until 1829.

Before the Metropolitan Police came the Bow Street Runners, who served the magistrate at Bow Street, Henry Fielding and then his half-brother, John. The Runners pioneered systemic crime investigations through information-gathering. The Runners also had horseback and pedestrian patrols.

By the 1820s, their reputation suffered because of association with unsavory people to retrieve stolen property. They were disbanded 10 years after the police force was established in 1829.

The new force wore blue uniforms to distinguish themselves from the red uniform of the army. Initially its role was crime prevention, until a long delay in finding a murderer led to the creation of a department of crime-solving detectives. Scotland Yard became shorthand for detectives, but it was actually the address of the police force headquarters.

Charles Dickens and the Bleak House Detective

Charles Dickens created the detective character Mr. Bucket in his novel, “Bleak House.” He was modeled after a real person. The character was a hit with readers, so more stories with detectives emerged from other writers.

Other Writers Follow

Wilkie Collins’ “The Moonstone” was published in 1868, preceded in 1862 by “Ruth the Betrayer” with the female detective Ruth Trail working in a Secret Intelligence Office established by a former police officer.

Another female detective appeared later in “Revelations of a Female Detective” by Andrew Forrester. In “The Boy Detective,” Ernest Keen emerged in the penny-dreadfuls.

In 1840s, the First Detectives in America Emerged in Boston

Boston detectives were modeled on what had been introduced in London, but the Boston police department was established later, in 1854.

Poe Inaugurated Crime Fiction in 1843

In America, the first crime fiction was “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” by Edgar Allan Poe, published in 1841. In 1855, Emile Gaboriau’s crime novel, “L’Affair Lerouge” was published and became very popular. The first American-based story, “The Leavenworth Case” by Anna Katherine Green was published in 1878. Her book was preceded by the translated French book, “The Widow Lerouge” in 1878.

A deluge of detective fiction followed the 1887 story by A. Conan Doyle, “A Study in Scarlet,” published in The Strand, a popular magazine. Since then police detective fiction has become a global phenomenon.

- Published in Writing & Editing Resources

The Institute of American Indian Arts Nurtures Native American and Indigenous Writers

The Santa Fe-based Institute of American Indian Arts (“IAIA”) provides a Native American art and culture-centric curriculum. Since 2012, the IAIA has offered a MFA in creative writing. In 2014, IAIA established a bi-annual writers’ festival; and in 2017, it awarded its first Sherman Alexie Scholarship of $7,500 per semester.

A Unique Institution

IAIA is the only multi-tribal higher education institution in the country, originally established in 1962 as an art-focused high school. This unique institution is dedicated to the study, creative application, contemporary expression, and preservation of Native American culture and art. Indigenous students from the U.S, Canada and other countries benefit from what the Institute has to offer.

IAIA also offers Associate and Bachelor degrees in Indigenous liberal studies, creative writing, the cinematic arts and technology, studio arts, and museum studies. The MFA program in creative writing is a low-residency program (requiring five residencies) that also provides off-campus online education.

MFA in Creative Writing

The MFA in creative writing program allows writers to work on their craft and learn more about the process of getting published and associated issues. Sherman Alexie teaches for the program, and do two of its first graduates, Terese Marie Mailhot and Tommy Orange. Mailhot and Orange are also the authors of the critically acclaimed “Heart Berries,” a memoir, and novel “There There,” respectively.

First Sherman Alexie Scholarship Recipient

The Sherman Alexie Scholarship’s first recipient, Jamie Natonabah, a Diné, is an alumnus of the IAIA, whose favored medium is poetry. She already has a distinguished resume. She is a winner of the New Mexico Slam Poetry Competition. “Red Ink: An International Journal of Indigenous Literature, Arts & Humanities” has published her work. She has also contributed to “Bone Light” and “Fourth World Rising,” two of IAIA’s literary anthologies.

Chelsea Hicks Bryan, an Osage, and Grace Randolph, a Wampanoag, were selected as runner-up and third-place recipients of the award, respectively. The MFA program provided more than $200,000 in scholarship money in 2017, including the Alexie scholarship.

Applicants for the annually awarded scholarship must belong to a Native American tribe or First Nation and submit a work sample. The deadline for the 2018 award was February 15.

The IAIA provides terrific Associate, BA, and MFA programs for Indigenous writers to help them improve and refine their skills. Since the 1970s, Native American writers have increasingly published their work for an English-reading audience. The IAIA wants to build on that foundation and nurture more talent by offering dedicated educational programs. However, since its expertise is also open to non-American writers, Indigenous writers who may not have such educational opportunities in their home countries should take advantage of IAIA opportunities.

- Published in Writing & Editing Resources

Popular Crime Fiction Sub-Genres

Crime fiction usually involves solving a mystery or why it occurred (such as “Crime and Punishment” by Dostoevsky and “Chanson Douce” by Leila Slimani). Crime fiction captivates readers by engaging their curiosity and desire to solve puzzles, and providing escapist entertainment that offers a break from their mundane lives or touches an inner fear they have harbored (for example, untrustworthy mates, killer nannies, and death by medicine).

From Poe to a Niche All its Own

Since the 1841 publication of Edgar Allan Poe’s, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” crime fiction has blossomed to become a genre with an ever-expanding community of writers. A US phenomenon before it crossed the Atlantic, crime fiction was a recognized genre by the 20th century.

The Sub-Genres of Crime Fiction

The genre has evolved over the years to include several sub-genres. The most popular sub-genres are:

The Cozy Mystery—In this sub-genre the detective is usually not a professional, the violence is not graphically described and usually not visible, and the story often has a small-town or rural setting. The sleuth is typically an intuitive and intelligent woman whose professional connections may aid her deductive skills. In this genre the focus is on character development and plot. Think Agatha Christie and her Miss Marple character.

General Suspense—This usually involves an ordinary person whose need to solve a problem sometimes involves finding a way to exonerate themselves. Think Gillian Flynn, Lee Child, and Dennis Lehane.

Private Detective Stories—In this sub-genre, the detective often works in a notable city, and there is explicit violence. Think Mike Hammer, the detective imagined by Mickey Spillane. Modern examples include Sue Grafton’s character Kinsey Milhone, Lawrence Block’s character Matt Scudder, and Janet Evanovich’s character Stephanie Plum.

Police Stories—Think James Patterson’s character Alex Cross, Ian Rankin’s character Rebus, and Michael Connelly’s character Harry Bosch. The protagonists’ stories include professional and personal issues, not just the actual crime that sets the stage.

Legal Thrillers—Think Scott Turow’s and John Grisham’s stories. The writers are often trained lawyers with a talent for creative writing. For example, Turow not only once taught creative writing at Stanford but is also a Harvard Law School graduate.

The Medical Thriller— These are usually set in a hospital, and the story involves medicine or its effect on an actual character. Think Michael Crichton, Robin Cooke, and Tess Gerritsen.

The Forensic Thriller—Such stories usually have a protagonist who is a pathologist or a scientist. Think Patricia Cornwell, Jeffery Deaver, and Kathy Reichs.

The Military Thriller—In this sub-genre the protagonist typically is in government service or a former serviceman. Think Tom Clancy.

Writers who want a career should try crime fiction. To write proper crime fiction, read crime fiction. Joining a writing group or an association, signing up for one or more workshops, and taking classes will also boost writing skills.

- Published in Writing & Editing Resources

Take Advantage of the Excellent Guidance provided by The Institute of Children’s Literature

Children’s literature has been a distinctive genre for more than two centuries. However, it has arguably never been as popular as it is today. For trade-specific knowledge needed to succeed in writing for this genre, you need a reputable source of guidance.

About The Institute of Children’s Literature

The Institute of Children’s Literature (“ICL”) provides stellar education for writers who want to write for a young audience. ICL provides guidance that covers all the subgenres and angles of writing for children and young adults.

The ICL has helped writers become better at writing for young readers since January 1969. In addition, ICL provides expert guidance about optimizing marketing. An average of 300 ICL students per year have their writing published.

One-on-One Instruction

ICL offers rare one-on-one instruction and guidance by a writer or editor experienced in the craft of children’s literature. Instructors develop their teaching plans based on students’ skill levels.

ICL Course Offerings

The coursework is designed for anyone who is interested in writing for a young reader, including parents, working professionals, and individuals who require flexibility.

Current courses are Writing for Children and Teens; Breaking into Print; Shape, Write and Sell Your Novel; and advanced courses: Beyond The Basics: Creating And Selling Short Stories and Articles and Writing And Selling Children’s Books;.

Learn from Experienced Professionals

All ICL instructors are published writers or editors. They have written a combined total of more than 900 books as well as more than 20,000 articles and stories that have been published by newspapers, national magazines and online. ICL matches its students with instructors according to student interests and needs. Placement depends on whether the student intends to write fiction or nonfiction, books, short stories, articles, or a combination thereof.

ICL’s Satisfied Students

On its website, ICL reveals that 89.7 percent of its graduate students were “very satisfied;” 98 percent would repeat the course; and 97.7 percent would recommend ICL to a friend.

Author Submissions for Feedback

The ICL is located in a beautiful Connecticut mansion. Writers can also submit writing for critiques through its website. People who cannot come to the physical location but would like feedback and marketing guidance can use the online resource.

A Weekly Informative Podcast

ICL’s director hosts the Writing for Children podcast. The podcast discusses the craft of children’s literature, including how to write a book, how to write for magazines, how to earn income, and how to get published. ICL experts answer listener questions. In addition, the show notes provide hard-to-access resources and useful links.

If you have stories you want to write for young readers and wish to excel in the genre, you will benefit from ICL’s expert guidance. Visit ICL’s website to learn more about the Institute and what it offers for writers in the Children’s and Young Adult Literature genres.

- Published in Writing & Editing Resources

Getting in Touch with Your Creativity as a Writer

If you are an avid fiction writer, then you have probably run into the problem of writer’s block once or twice. Lack of inspiration is the most potent enemy to a writer of any kind, but especially to one who relies on original tales and stories of fiction. Still, there are a number of ways you can get your creative juices flowing again, no matter how tapped out you feel.

Writers have a tendency to become stagnant in their work. They feel that the assignment at hand must be done as soon as possible, as many face impending deadlines for their work, but the fact remains that sitting behind your desk in your office is actually counter-productive to the creative process. To get the creative juices flowing, it is always a good place to start to get your actual, physical juices flowing: your blood. Try taking a short brake and going for a half an hour walk. We do some of our best thinking when we are walking, because we are getting more oxygen to our brains than by sitting behind a desk writing or typing.

Keep in mind that being sedentary is the enemy of creativity. Another thing you could do to combat mental and physical lethargy is to change your setting. Your desk and office may be the most congenial place for you to write logistically, but it may be stifling your imagination and creative capacities. If at all possible, set up shop in your backyard, on your deck, or at a nearby park. Try writing outdoors or simply change your work scenery to gain a different perspective.

This next pointer may be the most powerful yet: tap into your dreams. Even if, in your waking life, you are finding it hard to think creatively or come up with something new, chances are your subconscious mind is not having the same problem. It can be difficult, with your schedule, to record your dreams when you wake up in the morning, but give it a try. You can start by keeping a small notebook and a pen near your bed, perhaps on your nightstand every night. Wake up 15 minutes early every morning to give yourself time to simply lie in bed and think about your dreams. Close your eyes and try to recall every detail as best you can, no matter how seemingly inconsequential. Write everything down in the notebook—everything! This is the time where you should be a free-form recounting your dreams, and you can sift through the details and what is incomprehensible later.

You may get an idea for a new story form your dreams or maybe some valuable insight into a story you are already writing, as our dreams are often cryptic messages to us about things that are going on in our waking lives.

- Published in Writing & Editing Resources

Writing a Compelling Memoir

We all have stories to tell, from an awkward first kiss to overcoming a devastating illness. Memoirs are an excellent means of sharing the intriguing bits and pieces of our lives that have shaped who we are today. If you are ready to begin your own memoir, here are some tips to get you writing in the right direction.

Be Specific

A memoir is not an autobiography, which means that it should not cover your entire life. The objective of a memoir is to highlight a specific time period in your life or a specific event you experienced. Your memoir represents a single morsel or slice of your life.

Be Honest

Be truthful about the events you are describing. It might be tempting to write yourself in a more flattering light, but the memoir is not a work of fiction. Stick to the facts. It is perfectly okay to tell your story in an interesting way. Just be sure to avoid rewriting history. Telling tall tales is for fiction and readers will be skeptical anyway if you always have the right comeback at the right time.

Draw on Fiction

While it is important to be truthful in memoir writing, you still want the story to be interesting to readers. Try applying elements of fiction writing to your story without actually fictionalizing it. This can help you achieve a memoir that is both readable and memorable.

One place to start is with the people in your memoir, including yourself. Write about the individuals in your story as if they were characters in a novel. What are their struggles? Do they have any distinct characteristics? Draw on those aspects of the people in your story to help readers get to know them.

It Isn’t About You

It might be your memoir, but it should not necessarily be about you. Readers want to know what’s in it for them. What lessons can they learn from your story? What can they take away from it? Even though you are sharing an event or situation from your life, you do not want to sound like you’re just talking about yourself. Readers will quickly lose interest. Writer and instructor Marion Roach Smith says it best. “The best memoir is about something, and that something is not me.” Illustrate a universal theme, such as spirituality, through your memoir.

When composing your own memoir, remember to focus on a specific event or time period, stick to what really happened, utilize elements of fiction for interest, and emphasize a theme or lesson rather than yourself. Employing these tips in your memoir will make it one people want to read.

- Published in Writing & Editing Resources